The Grenadines Will Always Be Grenadian!

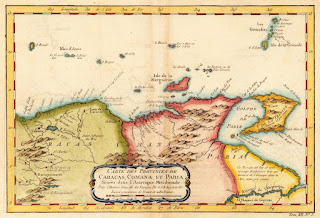

The Grenadines Will Always Be Grenadian! The Grenadines, from Bequia to Carriacou, were once entirely owned and administered by Grenada, hence their original name Granada y Granadillos (<AmSp Granada + illos: “little Grenadas”). A few of the approximately 125 small islands, islets, and rocks were first settled by the French in the mid-1700s, the last islands to be colonized by Europeans, most likely due to their small size, arid landscape, and the absence of yearlong streams. Today, Carriacou, Petite Martinique, Ronde, and some 30 small islets are dependencies of Grenada. The rest are now part of St. Vincent. Map of the southern Caribbean by Johannes van Keulen, 1684, showing the Grenadines’ early association with Grenada (note, the top is facing west; Grenada is colored red). In 1784, the Grenadines were officially partitioned on the recommendation of Lieutenant Governor Valentine Morris of St. Vincent who believed that the islands, especially those closer to his island, would be better served administratively and for security reasons if transferred to St. Vincent. Following the outbreak of the War of American Independence, Governor Morris had become weary that if Grenada was returned to the French while St. Vincent remained British, then the French would be too close at Bequia and thus threaten British St. Vincent. Although Grenada remained a British possession (barring a brief French takeover from 1779-1783), a buffer was created where all islands south and inclusive of Carriacou remained with Grenada, while Union Island and all islands north of Carriacou transferred to St Vincent. In 1784, Edward Matthew was appointed as “Governor-in-Chief in and over our Island of Grenada, and the Islands commonly called the Grenadines to the southward of the Island of Carriacou, and including that Island and lying between the same, and the said Island of Grenada.” It is interesting to note that, because of the size of Carriacou, the total area given to both countries was almost the same. The local story that the line separating Carriacou from St. Vincent goes through Gun Point, Carriacou (meaning it is technically owned by St. Vincent) is not supported by the available evidence. However, there might be something else to that tale that has since been lost. Grenada and the Grenadines by JN Bellin, 1765 St. Vincent subsequently included the Grenadines in its official name, “St. Vincent and the Grenadines.” Grenada, though known historically as Grenada and the Grenadines, is officially the state of Grenada. A similar name change to incorporate the two other members of the tri-island state was rejected in a national referendum in 2016, but hopefully, Grenada’s official name will one day include Carriacou and Petite Martinique. Regardless, because of their name, the Grenadines will always be associated with Grenada!

Le Bourg du Grand Marquis

Le Bourg du Grand Marquis History, Uncategorized July 10, 2024 What do the ruins in this village tell us about Grenada’s history? The name “Marquis” was quite common in 17th century France (also used as a title for nobility), and several colonists of the La Grenade colony carried the name. For instance, “Fort Marquis” in Beausejour (yes, Beausejour) was named after its commander Lieutenant Le Marquis (later convicted for assisting a rebellion with one Major Le Fort). It was also the name given to an indigenous “Captain” on the eastern side of the island who presumably lived in the area of Marquis, St. Andrew today.1 The remains of his village were mostly destroyed when the French town of Grand Marquis was built, but there are still some remnants left. Indeed, unbeknownst to most people, the pre-Columbian site at Grand Marquis is one of only a handful that date before ~AD 500 in Grenada. Figure 1: Some artifacts from the Grand Marquis site (GREN-A-2, Hanna 2019) The Earliest Human Presence In 1992 (and again in 1994), archaeologist Anne Cody surveyed along the Little St. Andrew’s River behind the ruins of the old French church in Marquis (Cody Holdren 1998).2 She recovered diagnostic Saladoid-Barrancoid pottery (AD 100-750) as well as later period artifacts; she also noted historical references to Amerindians in the area at the time of French settlement after 1649. In 2018 and 2019, Hanna confirmed the location of the site and took several surface collections and soil samples. As Cody had noted, the recovered artifacts included a wide breadth of pottery including white-on-red (WOR), zone-incised-crosshatching (ZIC), “scratched” wares, circular and coffee-bean eye adornos, and a small fragment of unworked amethyst (Figure 1). Historic bottles and ceramics were also found, mostly on the southern side of the river. Many of the ceramics had large inclusions, but given the amethyst, WOR, and ZIC, it appears likely that the site began during the late Saladoid-Barrancoid period (~AD 500-750), albeit with a strong Troumassan component later (~AD750-900). Unfortunately, two samples submitted for radiocarbon dating were actually hornblende (not charcoal), leaving the site’s chronology less grounded. So at present, the estimated period of occupation is AD 500-900. Historical Footnotes While the limited archaeological work has not borne evidence of occupation after ~AD 900, there is ethnohistoric evidence, as noted above, that Amerindians were present in the area at the time of French settlement. This is also suggested on the earliest known map of Grenada, drawn by François Blondel in 1667, which places two house symbols near the name “Grand Anse du Marquis” (Figure 2). Since no French settlers were in that area at the time, the house symbols represent Amerindian villages (Hofman et al. 2019). Figure 2: Clip of Blondel’s 1667 Map of Grenada; the house symbols represent Amerindian villages In late 1650, the village of “Captain Marquis” was attacked by then Governor Jean Le Comte. The Amerindians had fled, so the French “only found the carbets that they burnt, and then ruined everything,” (Anonymous [Benigne Bresson] 1975:17). In 1654, Le Comte again attacked a village in “Fond du Marquis” (ostensibly the same village, rebuilt). This time, “eighty savages were massacred…and the carbets and the huts were set on fire; everything that could not be carried was broken and destroyed,” (Anonymous [Benigne Bresson] 1975:41–42). Ironically, after the victory, Le Comte decided to row back to Fort Marquis (again, Beausejour) via the northern route, around Fort d’Esnambuc (atop le Morne aux Sauteurs). He hit a storm, crashed on some rocks, and drowned along with eight others.3 Figure 3: Map of Grand Marquis by Jean-Baptiste Le Romain (1748) The Marquis Church Ruins It is possible that a nearby site at Marquis River (also identified by Cody but not well-studied) is the historic-era Amerindian site rather than Grand Marquis (although the Blondel map shows two villages). Either way, within the next 50 years, French settlers had established the town of Grand Marquis atop the earlier Amerindian sites, which then became a major port town in the eponymous Parish of Grand Marquis (now St. Andrew) (Martin 2013). On the 1748 Romain map above (Figure 3), it is clear that the early town was focused along the main road. There were several churches, but the one marked “B” is the one still partially standing (Figure 4). This is clear after we georectify the map onto a modern satellite image (Figure 5). The GPS point taken at the church altar is exactly where the “nouvelle eglise” stood – the new church in 1748, much larger than the others. Figure 4: Old church wall and altar in Marquis (Hanna 2018) Interestingly, the church image on the 1748 map is not just a symbol but an actual layout of the church. It matches the size and orientation of the remains today, including a semi-circular back wall (perhaps an apse, although the structure has not been mapped). It is unclear why the new church was built so far from everything else, but the town was expanding by then. Additionally, the lagoon behind the town indicates the area was prone to flooding. Indeed, although it was eventually filled in, the area is very flat and still prone to flooding today (hence the Bumpy Corner nearby perhaps?). Figure 5: Romain 1748 map georectified onto a modern satellite map (modern roads and rivers highlighted, as well as nearby archaeological sites) Fédon’s Rebellion Before dawn on March 3, 1795, Julien Fédon and a gang of other French planters descended on the town of La Baye (Grenville), dragged the men from their beds, and hacked them up with cutlasses in the streets. They then torched the town and several British plantations on their way to other conquests, triggering Fédon’s Rebellion. It is sometimes said that the March 3 attack was actually on Marquis (not La Baye, 3 miles to the north). Some authors have even suggested the name had changed from Marquis to Grenville and then the town moved after it was burned down, but they

Marking an ‘X’: Exploring the History of Grenada’s Surnames

Marking an ‘X’: Exploring the History of Grenada’s Surnames Travel July 10, 2024 Angus Despite the widespread belief that most Grenadian surnames today are derived from plantation/slave owners, many former enslaved men actually used their first (and only) names to create their family names. This is the case for a plurality of both English and French-derived surnames today. That means your surname may contain a clue to the name of your last enslaved male ancestor. A smaller percentage of Grenadian surnames, both English and French, are derived from plantation owners, and this often indicates a blood connection. Maybe we can see these surnames as more a creation of the newly freed Grenadians to establish identity, rather than something imposed upon them, as was the case in other countries. Malcolm X, the son of Grenadian Louise Langdon Norton Little (1895/6-1989), made famous the identity struggles of Black people in the diaspora when he replaced his family name of Little (or what has also been termed his “slave name”) with an ‘X’ to signify his lost or robbed African identity as a result of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the legacy of slavery. It is a cry voiced by many descendants of enslaved Africans in the Caribbean who feel a sense of loss, a sense of disconnect, not knowing their African name, their African identity. In the 1970s, following the emergence of Rastafari and the Black Power Movement, several Grenadians adopted African names (like Akee, Kamau and Owusu) in an attempt to reclaim that perceived lost identity, adorned with their dashiki and a big Afro, even carrying around beautifully carved afro-combs to enhance that identity. The recent developments in DNA technology have provided some solace in creating a “direct” biological connection to the peoples of West Africa, but the connections to ancestral birthplaces remain elusive at best. Yet, many continue to search their ancestry for any links that would take them closer to finding that lost identity. For Grenadians (and others from the Caribbean), doing genealogical research is difficult to say the least. Luck is the most operative word here: luck in locating pertinent records, luck that the records have not been eaten by time, luck that you can read the handwriting, etc. It is often easier for Grenadians in the diaspora because many of our records are available in the US, UK and other places. Grenada has outsourced the preservation of its history to others! For those making that difficult search because of the dearth of records, archives, and access to whatever might be available, I would like to share my thoughts on a very important aspect of that search from my years of experience in my own family search and as a historian and archivist working among those historical records. I am referring specifically to the origin and history of the surnames of Grenadians, which I hope will aid you in your search and overall understanding of Grenadian genealogy. Slave Registers and Surnames It is often repeated that most Grenadians (and West Indians) today have family names that were unwittingly received from their enslaved ancestors’ masters/owners, hence the reference to family names as “slave names” and Malcolm X’s use of an “X” to illustrate that. However, that is only true for a minority of Grenadian surnames (although it could be argued that all names of enslaved Africans are “slave names”). There is little on enslaved names and naming practices, which makes it rather difficult to trace Black ancestry beyond the limited official records like the Civil List (which begins in 1866) and selected church records, especially the Anglican Church (see Handler & Jacoby 1996). However, a look at the names of plantation owners (Legacies of British Slave-ownership) and the Slave Registers (Former British Colonial Dependencies…) makes clear that many of those names do not survive in Grenada as surnames, and when they do, there is an actual blood connection. In fact, the plurality of Grenadian family names today, and the most popular ones at least, are derived from the first names of the last enslaved male ancestors. This does not seem to be the case across the region (for example, in Trinidad, St. Lucia and Belize, enslaved were given last names on the Slave Registers; or in Curacao where former enslaved received surnames based on the first names of the wives of their white slave owners, hence the preponderance of female surnames). But for Grenada, an examination of family names today will reveal the preponderance of male first names. This in itself is not unusual, as many European cultures and patrilineal societies worldwide have used this naming practice for centuries (think of many names in the Bible – Solomon, son of David; Joseph, son of Jacob, etc.). What is unique about it here is how it came about in Grenada. Records of the names of enslaved Grenadians are readily available and give a good idea of the names that were given to enslaved peoples in Grenada. As a matter of fact, there are complete lists of the enslaved in Grenada between 1817 and 1834 as part of the Slave Registry Act passed to inhibit the continued illegal importation of captive Africans (Former British Colonial Dependencies…). Other lists are also available in legal deeds from the sale of plantations, which included enslaved as part of the property (Register of Records, 1764-1931). These lists provide a clear picture of the rendered/official names of the last generation or two of enslaved Grenadians. Comparing the list of surnames today with the Slave Registers reveal an obvious connection: a majority of the family names today were derived from the actual names held by the last enslaved males. They did not have actual surnames, so the Slave Registers recorded the patriarch’s first name. Table 1 provides a list of the 20 most common family names today and compares them to the prevalence of these names to their counterpart in the Slave Registers. Table 1. The 20 Most Common Grenadian Surnames Today and Their Prevalence in the Slave Registers Rank in Grenada