“Slave Pens” in Grenada? Finding Ancestry in the Historical Landscape

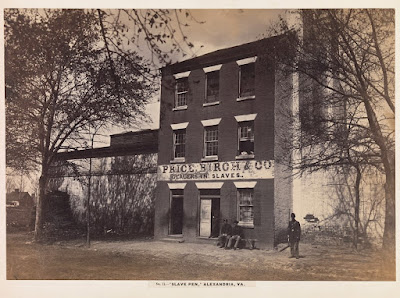

“Slave Pens” in Grenada? Finding Ancestry in the Historical Landscape ours of estates like Dougaldston, St John, or River Antoine and Belmont, St Patrick today will reveal little to nothing of slavery unless one has knowledge of what took place here beyond the cocoa trees, sugar-cane fields, and old waterwheel technology that dates to the 18th and 19th centuries (Figures 1, 2). There were no family heirlooms to pass down, no shackles or whips that tell of the brutality, no memory of tears that tell of the suffering, no ruins of thatched houses that reveal the hearth of everyday (enslaved) lives, no drums beating out rhythms of melancholy melodies, no cultural artifacts that linger in museums, and no monuments that sing praises to heroic ancestors. It is a landscape and heritage barren of slavery except in the enduring nightmare of it all. Figure 1. River Antoine estate in St Patrick still producing rum utilizing slavery-era technology in its waterwheel and aqueduct system (courtesy Grenada National Museum) The current relic landscape, particularly the plantations, reveals little of its slave past. The most noticeable are the few remaining “estate houses” or ruins that may tell a tale of the slave-owning families who resided there, but most were actually built post-Emancipation, having little or no connection to slavery itself. The decaying windmill towers, copper pots, rusted waterwheels and crumbling aqueducts that fueled centuries of production of sugar seem almost out of place today and little connected to that dark past (Figure 2). That brutal, dehumanizing system of forced and torturous servitude that ended 187 years ago. For the majority of Grenadians, the descendants of the islands’ enslaved, there is nothing in these idyllic, picturesque landscapes that reminds of the suffering their ancestors endured during slavery and that impact their lives even today. It is as if slavery never existed at all, or simply vanished with the changing landscape! Figure 2. Ruins of the abandoned (since 2004) waterwheel at Dunfermline Estate, St Andrew (photo by Angus Thompson, courtesy the Grenada National Trust) But Grenadians have nonetheless found at least three dark corners tucked into the architectural landscape that they have deemed places of significance in the enslavement of their ancestors. On the Hermitage and Mount Rich Plantations in St Patrick and on Melville Street in St George’s, they have identified what have become known as “Slave Pens” where many believe that enslaved Africans were held there for either security, punishment, breeding, or any variety of nefarious purposes. The cavernous and dark nature of these spaces signify to many the depravity of slavery, and have made these places reverential to the memory of brutalized lives. They are akin to tombs of the unknown to countless ancestors who we know so little of beyond a singular name, if at all. The belief is so widespread that these places are highlighted in official travel guides and listed on heritage maps of the island. Visitors are encouraged to explore where enslaved Grenadians purportedly endured unimaginable suffering, the only such sites available from that brutal past. There is, however, one problem with these places of remembrance (particularly those on the plantations): none actually date to pre-Emancipation times, let alone present evidence that they were ever used to house enslaved people for any reason. Slave Pens in the History of Atlantic SlaveryHistorically, the slave pen referred to a place for keeping captives confined, especially as a temporary holding facility for enslaved Africans on the West African coast in places like present-day Ghana, Sierra Leone (Figure 3), and Nigeria (Sayer 2021) while awaiting transportation to the Americas across the torturous Middle Passage. The use of the word “pen” is clearly illustrative of the regard and treatment meted out to those it imprisoned. These fenced and thatched sheds or “houses” were also known by the Spanish name barracoon (from Catalan for “hut” via Spanish barracón). It is interesting to note that the appearance in text of the word barracoon dates to circa 1840, but similar structures were widespread during the entire period of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Figure 3. “Slave Barracoon” in Sierra Leone, West Africa, c1840s (courtesy The Illustrated London News, 14 April 1849, v.14:237) In North America, a slave pen referred to a building where enslaved who ran away were confined following recapture, for sale or until transportation, the most infamous of which was in Alexandria, Virginia (as depicted in the movie 12 Years a Slave) (Figure 4). In Henry Bibb’s account as a slave in New Orleans, he describes the holding area as a “pen,” which can still be visited today (El-Shafei et al. nd). Figure 4. The façade of the Alexandria, Virginia, slave pen 1861–1865 (courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art) In the Caribbean, the early use of the term slave pen was reserved for places on islands like Curacao (by the Dutch) and the British Virgin Islands, which functioned as slave depots where captive Africans were publicly displayed for sale across the region. Though the term was not applied to specific buildings or institutions on plantations during slavery (but may have been used for confinement), several across the region have since been designated as such in attempts to (re)define the relic slave landscape. For example, as part of its Slave Route project, Guadeloupe identified as a place of memory, the “Slave Cell of Belmont Plantation.” According to the brochure, “This is a slave cell from the 18th century, which was used to lock up slaves who had been punished by the master of the estate…. Many plantations had a cell of this type…” (see Slave Cell of Belmont Plantation video and text). Another is at the Annaberg plantation on St John, USVI, where a “dungeon” cell still contains leg shackles and graffiti drawn by enslaved prisoners (Figure 5). Figure 5. The “dungeon” on the Annaberg plantation, St John, USVI (courtesy B. Mistretta, 2017) In St Lucia, there is a small stone building attached to the St Lucia Distillery in the Roseau valley and described as having been used as a “slave cell” or prison, one of